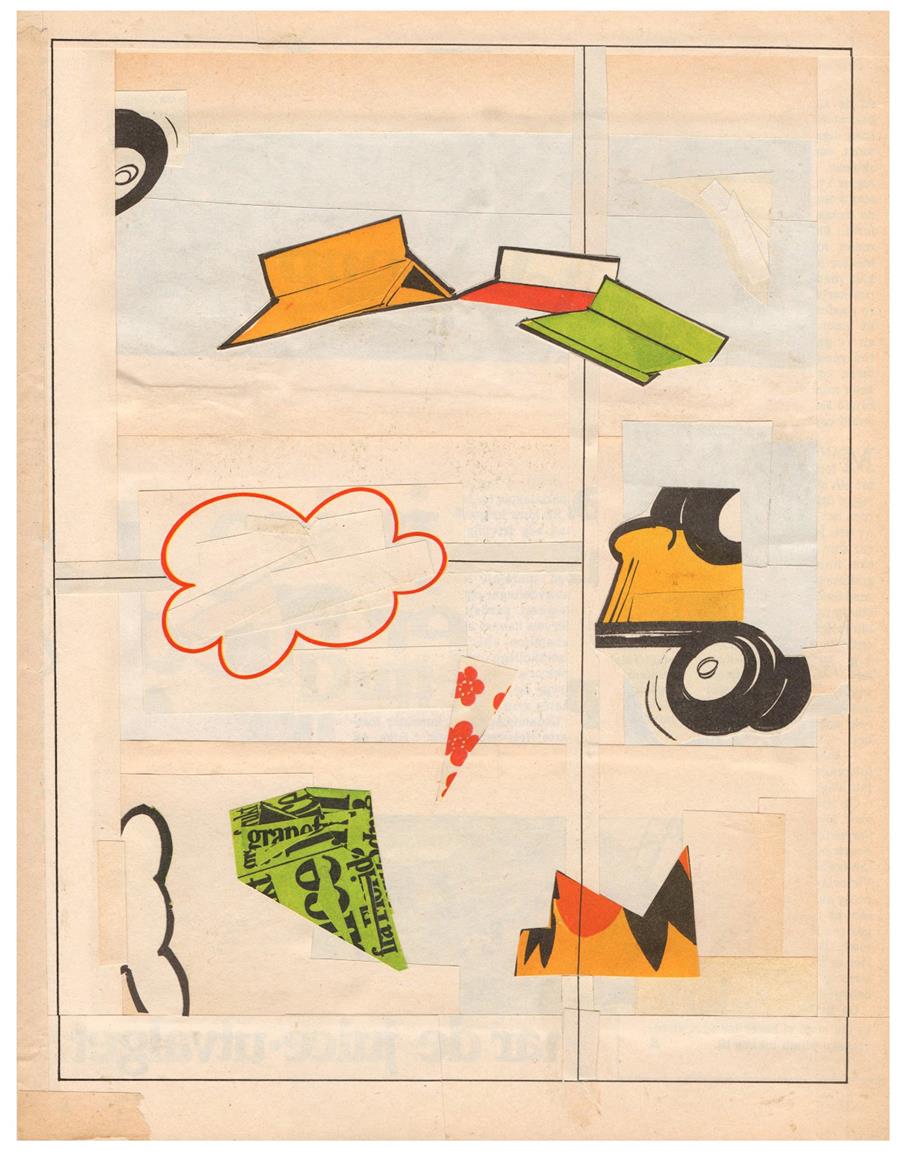

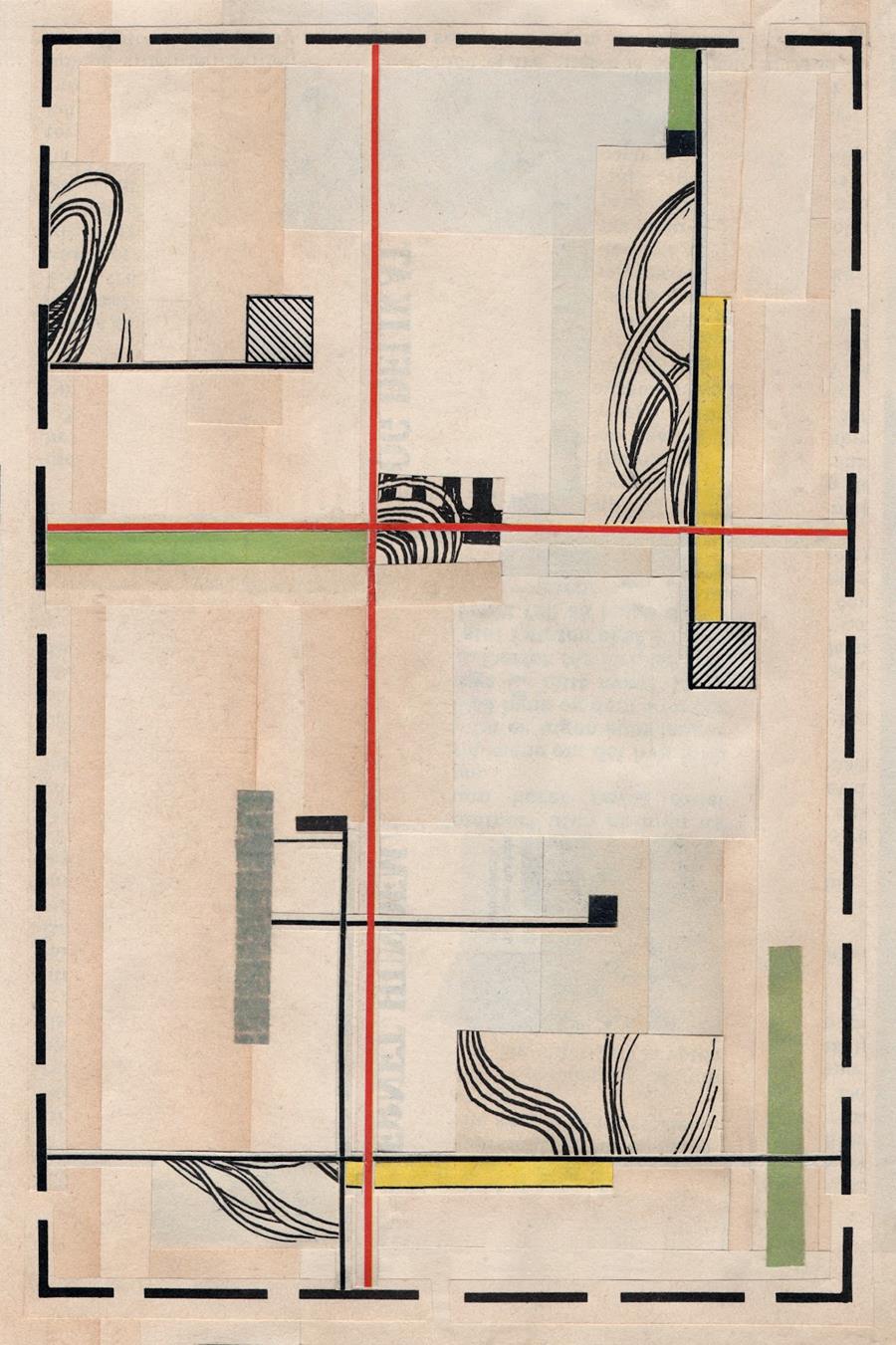

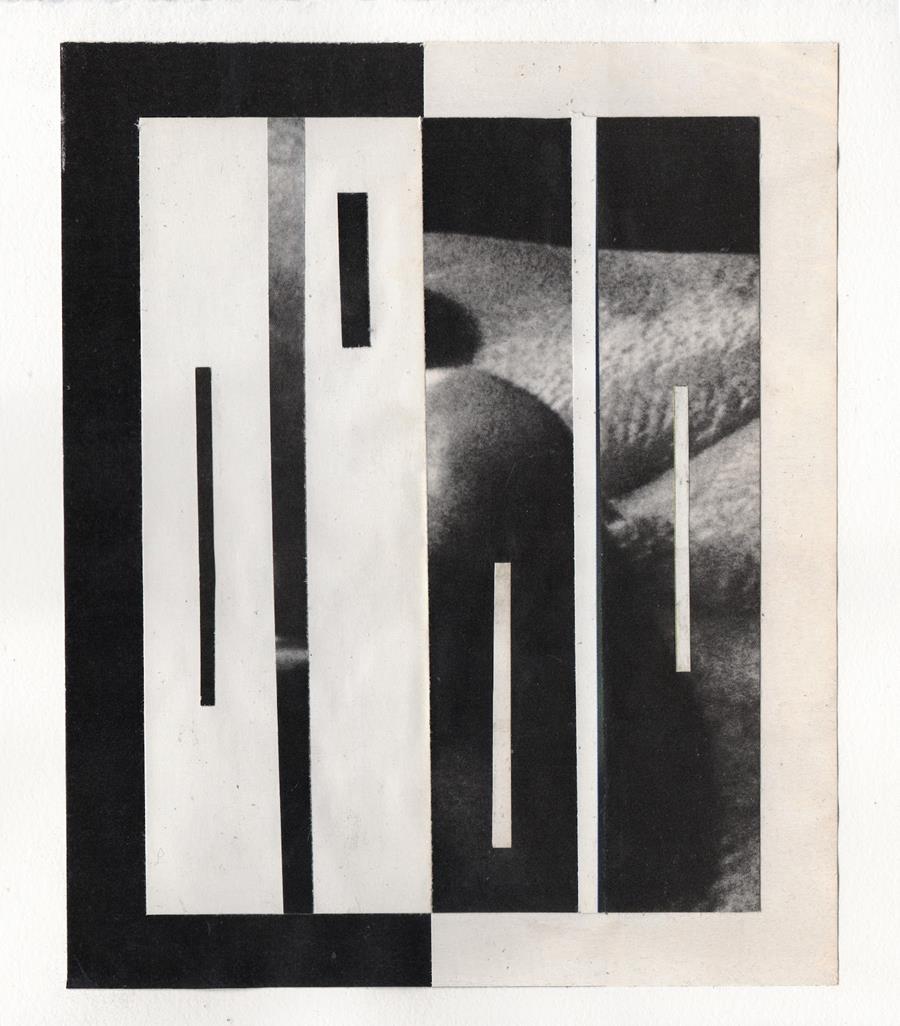

Paper collage

Jordan Bohannon

Jordan Bohannon works with collage as a practice of recontextualization, drawing on twentieth-century magazines and books as evidence of a media-saturated century. His background in design and editorial illustration sharpens his attention to figure and ground, to the grid, and to the way structure can produce open-ended meaning rather than closure. Rejecting nostalgia and the easy seductions of recognizable imagery, he builds compositions from atmospheres and fragments that resist quick interpretation.

In the Words of the Artist

Paper collage

When I was younger, I admittedly hated collage. I saw it as a cheap style, an aesthetic signifier capable only of a contrived kind of edginess. A collection of essays by Aaron Rose, Mandy Kahn, and Brian Roettinger titled Collage Culture—which argues that the twenty-first century suffers an identity crisis as a result of the cultural prevalence of collage without an equally applied consideration of tone, history, and meaning—confirmed and codified my contempt.

It wasn’t until I started reading post-modern literature that I understood the artistic potential of collage. Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow—with its pastiche of tones and styles, unattributed quotes, layers of allusion, appropriations of popular forms, and amalgam of source materials ranging from Rainer Maria Rilke to Looney Toons—laid bare for me the strategies of constructive reinterpretation afforded by the medium.

After moving into my first apartment in Tucson, Arizona, I subscribed to the Sunday paper. Before long, a pile of papers had accumulated in the corner. I wanted to be an author, but I was struggling to realize my artistic vision through writing. One day, perhaps out of frustration, I decided to spend some time collaging to clear my mind. As time passed, I found myself collaging every day, making dozens of works at a time in frenzied bursts. Years later, I am glad to have found that the practice has stuck.

Paper collage

I hold space for intuition; spontaneity sharpens the eye and mind. But a good eye is never enough. Impulse cannot substitute for intention.

The first thing I do in the studio is make five small collages as quickly as possible using only two pages of material from my scrap pile. This exercise exorcises ideas both good and bad; once the five are complete, I make notes on each. “What is successful?” “What went wrong?” “What did I learn?”

On the walls of my studio, I have what I call Blanks taped up. These are rectangles of neutral backgrounds adhered to larger sheets of paper. I will stare at their emptiness for weeks or months while a conceit comes to me to pursue. As I work to fill the Blanks, I rehang the artworks on the walls. Placing the finished work in relationship to the remaining Blanks, ripe with absence, helps me determine what needs to happen next.

I have dozens of folders filled with images that I’ve grouped and left to marinate—some for years now. When searching for material to work with, I will often come across something so potent that I cannot immediately make use of it.

I keep numerous unfinished works floating about my studio. I require time to weigh compositions; add, subtract elements; reflect on balances, tensions. I’ll often find unfinished works sandwiched between cutting mats, stacks of paper, and piles of books. Such surprises afford me the opportunity to evaluate incomplete work and to decide whether to return to that line of inquiry or salvage the materials and start anew.

Paper collage

Each time I pick up my knife, I am trying to cut through my immediate contexts, varied influences, and the noise of everyday life and to find a kernel of personal truth.

Practicing collage has strengthened my convictions that:

- All art is political (even if those politics aren’t considered, or good).

- There are multiple truths, no single history.

- Objectivity is a myth; subjectivity is the only approach to reality that can account for eight billion lives.

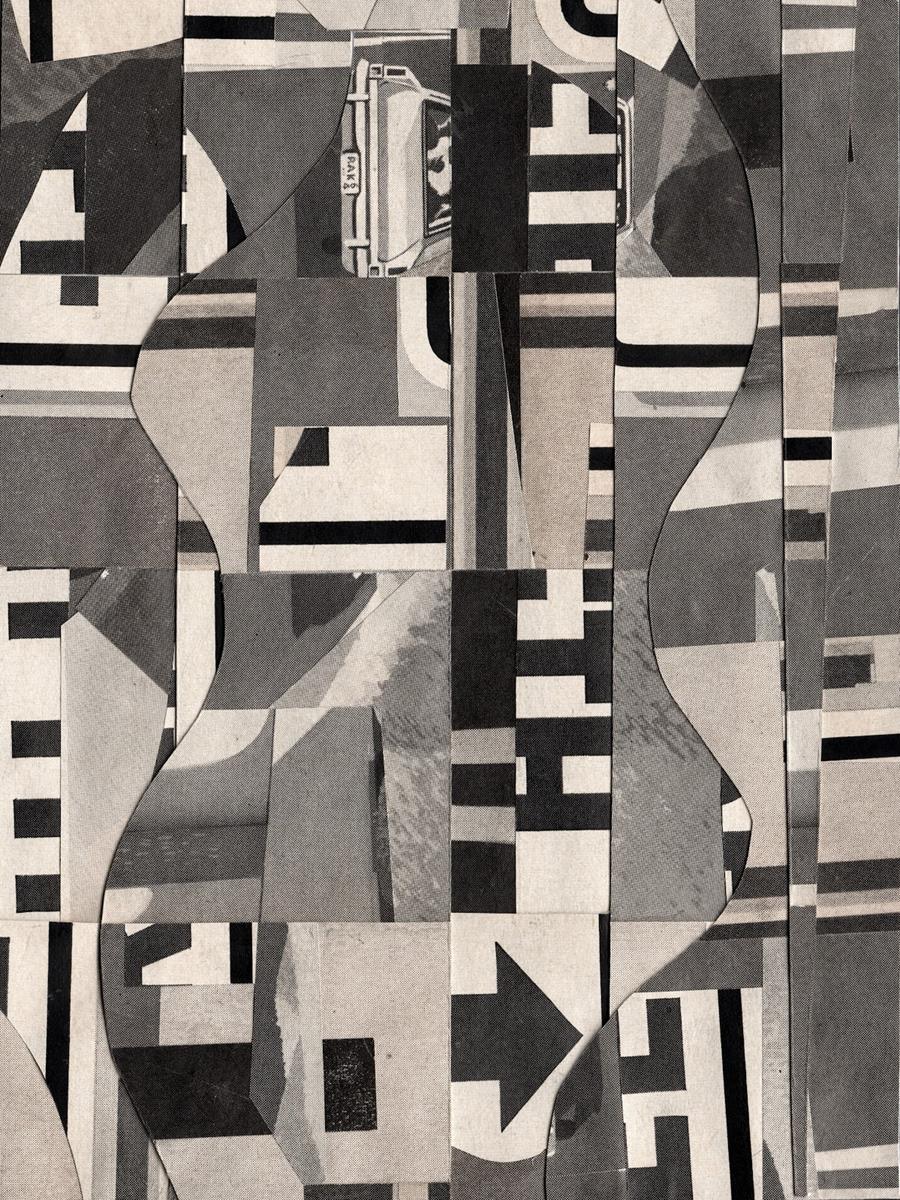

Over the years of refining my practice, I’ve come to terms with the central position that grid systems occupy in my daily life. I live and die by the grid; it is the tool by which I order my environment, thoughts, and self. In all things, the grid is implied; it’s always there, whether one recognizes it or not.

This compulsion towards organization, to make sense of what I see and what I think, manifests itself in my work. When I sit before a blank page, I am confident in my approach towards establishing a structure. Once the structure exists, from within those confines emerges an open-endedness, a sense of infinite possibility.

My affinity for grid systems is perhaps a consequence of being raised in Phoenix, Arizona—that sprawling anti-city in the Sonoran Desert with its seemingly endless expanse mapped onto a Cartesian plane.

Paper collage

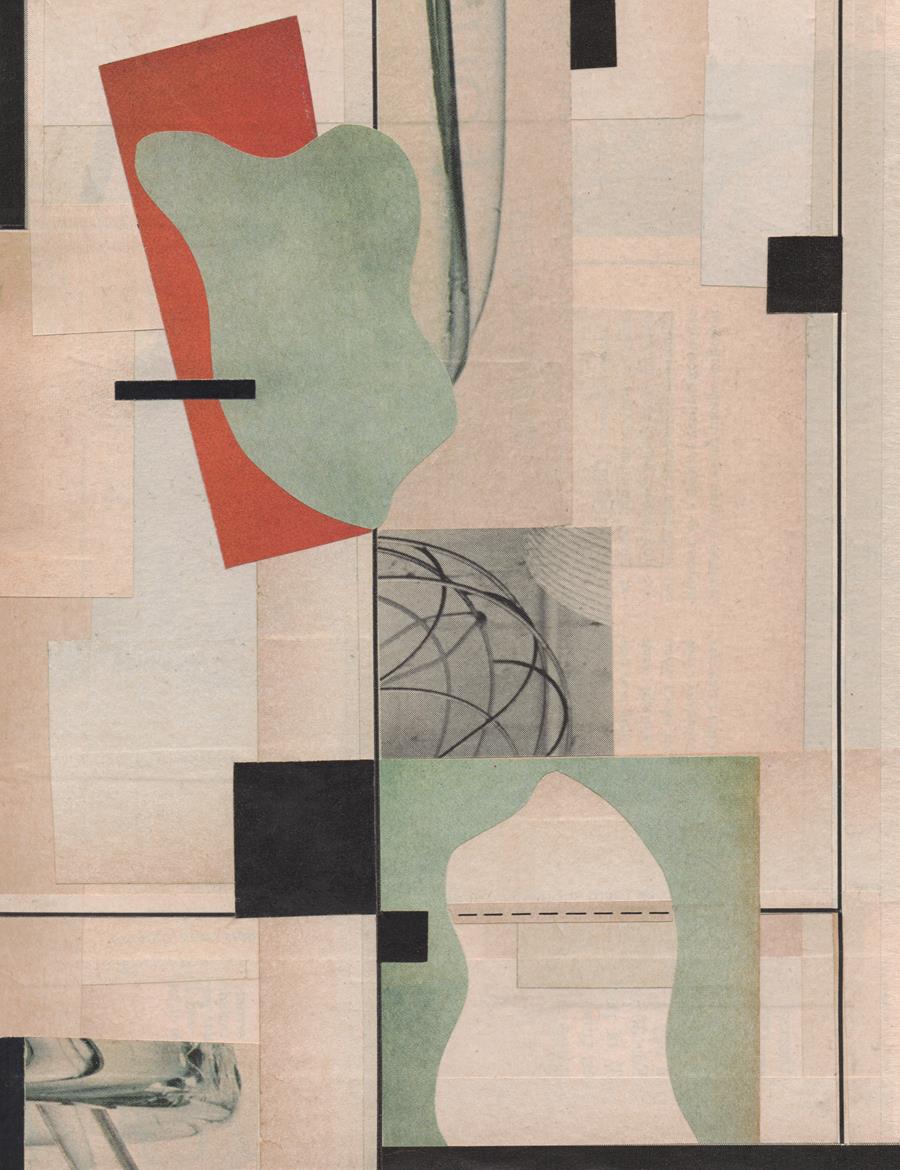

I work almost entirely with material from the twentieth century. I pick up old books and magazines whenever I come across them, but I avoid using anything that could be considered precious, valuable, or rare.

Though I work with vintage materials, I loathe nostalgia and the outsized position it holds as a cultural engine; it is the cheapest of sentiments. My interest in the twentieth century stems from a desire to interrogate the advent of our media-saturated culture. The pace at which technologies progress all but forces us to forget how recent a development mass media is. It is only within the last century that people began reading the same magazines, watching the same television programs, tuning into the same broadcasts, all taking up residence in McLuhan’s global village.

This is the context within which I approach my materials. Life magazine—my favorite material—offers to the twenty-first-century reader a dizzying view of the landfill of American life. Beneath the gleam of the advertisements and full-color photo essays is a chilling snapshot of mid-century American hegemony. Each page, read today, reveals the faded blueprint by which a national identity—a dominant culture, thriving with the conveniences afforded by capitalism—was to be constructed, as both shield and sword against the existential threats posed by the Cold War.

A critique of the medium that I heard years ago and have since internalized is that a collage is only good as the material used to make it. Beauty in, beauty out, as it were. It is not enough to find an image depicting a conventionally attractive person, place or thing, decorate that image with graphic elements, and then call it art.

As a rule, I avoid incorporating the human figure into my work. Cutting up pictures of people is a violent act. To what end is this violence applied?

I favor instead the abstracted, the ephemeral. A fragment of a familiar object, the lonesome expanse of a sky, the background of an advertisement, the margins of a page, the shadows in the corner of a room. I prefer the edge of a photograph, the background of an image so thoroughly decontextualized that there is not a chance of the viewer possibly knowing what it once was. There is an impulse in many to read a work of art—to decipher symbols, connect the dots, pick up on deeper meanings. My aim is to make work that resists such readability.

Paper collage

The future of collage has always been, and will always be, analog. The collages of today that will transcend both time and trend are those conceived of with cunning and care and fashioned by the deft hands of artists who take seriously their craft.

The future of collage is crisis. There have never been more artists, but the collective output has never seemed so much the same. The dominant mode of artistic distribution being digital, artists in search of audiences must participate on platforms that confuse art for content. There are countless artists working diligently, but too many labor to create works that employ a visual language that caters to the corporations that have monetized not only our attention spans, but more importantly, our tastes.

The future of collage is with the archivists. Two of the most memorable works of contemporary collage I’ve experienced are Carmen Winant’s Pictures of Women Working (2016–2021), a wall-sized collage comprised of hundreds of photographs, and Carla Liesching’s Good Hope (2022), vertical columns of images chemically transferred onto delicate fabric. Both artists refrained from intervening directly with their images, instead allowing the collection and presentation of images to serve as the catalyst for de/recontextualization.

The future of collage cannot be found in the past. Works like those by Winant and Liesching are far more interesting than anything made by someone who treads the water poured out by the greats: Hannah Hoch, Kurt Schwitters, Robert Rauschenberg, Raymund Saunders, Barbara Kruger, the list goes on. These artists are rightly celebrated, but for the artist practicing today, there is more to learn from these artists’ ethos and writings than from their visual strategies and individual styles.

Paper collage

I studied visual communication and have worked as a designer. While design and art have different objectives, both practices are predicated on the act of seeing. The basic elements of design—composition, contrast, color, proportion, balance, scale, line, texture—are essential to any artist’s success.

There are two specific elements of design that I consider frequently in my practice: figure/ground contrast and the grid system. Figure/ground contrast refers to how a subject is situated against a background, both occupying the pictorial plane. In collage, the ground is just as, if not more, important than the subject. A collage cannot be successful if the figure/ground relationship is non-existent or unbalanced. A well-executed grid system can guide a viewer through the visual experience. For the artist, the grid offers a framework to operate within and without.

I have had the pleasure of working with several preeminent publications. The nature of this work, editorial illustration, is quite different from my personal practice. What makes an editorial collage successful is the work’s ability to communicate key elements of a story while enticing potential readers. What makes for a successful work of art is a much more open-ended matter.

Intrinsic to editorial work is collaboration. Any work that is published has been reviewed by an art director, and often a team of editors, who provide feedback and push the illustrator to make the best possible piece. I’ve learned a great deal from every AD I’ve worked with—those relationships, and the feedback I’ve received, are among the most rewarding parts of the work.

About the Artist

Jordan Bohannon (b. 1994) is an artist based in Pittsburgh, PA. He has worked as a digital marketer, graphic designer, editorial assistant, illustrator, screen printer, barista, and dry cleaner. His work has appeared online and in print in The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg, and The Baffler.

For Your Viewing Pleasure

What to watch, read, and experience, as curated by the Collé team.

RUBYDOESDESIGN is a designer based on the south coast of England, creating engaging graphics that help clients grow and connect with their audiences. Whether supporting a business looking to extend its reach, developing visuals for a major upcoming project, or crafting the perfect artwork to bring a space to life, she brings a thoughtful, client-focused approach to every commission.

COLIN HUNTER is a graphic designer and event professional based in Pittsburgh. He specializes in brand design and has experience across a variety of industries. He currently works as a Designer for The Atlantic.

STEPHEN KNEZOVICH is a Pittsburgh-based collage artist who has been obscuring faces and obstructing landscapes since 2009. Working with discarded American mass-market news and lifestyle magazines, often from the pre-1960s, he uses analog cut-and-paste to render the familiar anonymous and to surface a quieter, beautiful strangeness.

GREGORY GRAY lives and works in Harlem, NY, as a full-time artist who loves making art and drawing inspiration from science fiction, history, and fantasy. He worked for over 30 years as an art director and graphic designer while painting and drawing.

London-born artist ANDY BURGESS, currently residing in Tucson, Arizona, is known for his renditions of modernist and mid-century architecture, panoramic cityscape paintings, and elaborate mosaic-like collages made from collected vintage papers and ephemera.

Out and About

What to watch, read, and experience, as curated by the Collé team.

▼ READ

Her Intricate Paper Cuttings Outsold Rembrandts. Who Was the Dutch Master Known as ‘Scissors Minerva’?

Joanna Koerten was a super star of the Dutch Golden Age. By Katie White on ArtNet.

▼ READ

These 7 Must-Read Books Unlock the World of Surrealism by Verity Babbs

Here's what you wanted to know about Surrealism manifestoes, the movement's under-sung women, and yes, Dalí's mustache.

▼ LISTEN

Tranquilizer by Oneohtrix Point Never

This new album by OPN is the kind of record that makes time feel elastic. It leans into a collage oriented compositions, uneasy and beautiful at once, with turns that reward a second listen.